Let me paraphrase a quote I cannot seem to find (if you know of it, please drop me a note). I recall someone once expressing a thought along this line: A new idea does not come so much as a eureka moment but as a series of small discoveries.

What I wrestle with in writing this blog is the process of hanging thoughts on a feeling — a kind of sense I have that there is an unexplored, significant, uniquely playful direction in which to take technology. At present, I can barely draw the boundaries of this notion and yet I can still feel its edges even as I struggle to put words to it. So recent days have been exciting as I’ve experienced several small discoveries in just what this idea of playful technology might mean.

The word playful is distinct from game and even from play.

For a long time I’ve made the natural association of the word playful with the word play. On its surface, it seems rather obvious. I’m beginning to think more deeply about this and seem to be moving to a richer understanding of these words. Play encompasses many expressions of the term, encompassing games and non-games alike. What if something that is a type of play is not necessarily playful?

English being both a language wonderfully descriptive but also at times quite ambiguous, let me get at this distinction with some simple questions. Can you imagine describing a game as playful? I bet you can. Can you also imagine describing a very different game without the word playful ever entering your mind? I know I can. Isn’t that interesting? If a game is a kind of play then how can one game be thought of as playful and another as something that’s not particularly playful? I posit this is because the semantics of playful and play are not nearly as related as we may think.

When I introduce the phrase “playful technologies”, the people to whom I’m speaking will invariably ask me to explain. For the last few months this is how I’ve started that conversation…

Me: “You know video games?”

Them: “Yeah?” (They say with a certain expectant, upward lilt of recognition.)

Me: “Okay. Not that.”

Slowly it’s begun to sink in that this is a more profound distinction than my pithy, if confounding, way of starting conversations might first seem. In fact, not realizing it, I began to get at this very notion a few months ago when I wrote about gaminess and ungames.

Playfulness embodies a sort of organic emergence.

In general, games are goal oriented. Their structure leads the player down a sometimes lengthy path bounded by a variety of rules to achieve some aim. The whole experience involves many layers of long-form design towards that end. Playful experiences are much different than this. At the core of something playful, there exists an emergence — a capacity to spark behaviors or experiences that very well may not have been designed or even intended, a complexity that arises from a multiplicity of simple interactions.

I recently read a transcript of a presentation given by Brian Eno entitled Composers as Gardeners that helped me see this. Eno’s central point is this:

My topic is the shift from “architect” to “gardener”, where “architect” stands for “someone who carries a full picture of the work before it is made”, to “gardener” standing for “someone who plants seeds and waits to see exactly what will come up”.

A game is architected. Something that is playful is “grown”. Grown in the sense that seeds are planted and at each interaction with a player those seeds instantaneously grow into forms and combinations not necessarily envisioned by the gardener. But just as elaborate architecture can include garden terraces, this distinction between games and playfulness does not preclude a game from including playfulness — hence the possibility of both games that are playful and games that are not. With its block-based world construction, Minecraft is a great example of a video game that is also very playful (and very popular because of it).

And now onto this business about cardboard boxes.

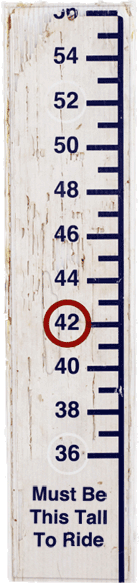

How many times have you heard the well worn trope about kids playing more with the box a toy came in than with the toy itself? Isn’t it interesting that something about this statement rings true however exaggerated it may be.

Blocks (and many other playful objects) have this emergent quality. There’s just enough there to play with but the experience has not been mapped out to a distinct endpoint as in a game. There exists just enough properties and interactions to allow combinations of simple interactions without end. In the very best kind of playfulness, there’s hints and suggestions as to how to play but nothing guiding or constricting that freeform expression. The player explores and combines what is already there. In my opinion, this is why so many technology-laden toys fall flat (see The Zen of Toy Blocks). The technology has been incorporated and a few specific interactions designed in such a way as to map out how to arrive at an endpoint. This is not the essence of playfulness, let alone much fun.

Technology added to games has opened an amazing new world. The same has not yet happened in playfulness. I’m certain I have not expressed my notions here with perfect clarity. And, of course, I’m still working these ideas out. That said, I believe the way forward is to explore playfulness as emergence through technology — using technology to imbue objects, spaces, and experiences with the seeds of many simple but emergent interactions. With technology, what has been limited by physical constraints in space or time can be made vastly more intricate. The goal is to not create something more complex. Rather, I’m proposing that playful technology involves the interweaving of a tremendous number of simple interactions that can be combined in compelling, enthralling, and very new ways only possible through technology.

(Image by Paul Lim under Creative Commons Licence)

Wednesday, January 25, 2012 at 1:39PM

Wednesday, January 25, 2012 at 1:39PM